america’s suburban experiment in microcosm

“Why did I take up stealing? To live better, to own things I couldn’t afford, to acquire this good taste that you now enjoy and which I should be very reluctant to give up.”

-To Catch a Thief [Alfred Hitchcock]

The cookie-cutter suburban lifestyle marketed to American families of the 1950’s sold the ‘American Dream’ of neatly packaged, idealized, and perfected act of material comforts. Sprawling to the outskirts of the city-center, the locked in environment and lifestyle presented the car as a necessity. The world view of suburban residents reduced to the aperture of the panoramic curved windshield of their car. The famous 1942 painting “Nighthawks” by Edward Hopper depicts a couple of together-alone coffee drinkers in a diner. The diner a symbol of the open road and its consumeristic anonymity scattered with glowing neon signs, ice cream sundaes with a bright red cherry topping, close encounters with the randomness of human, the subtle smell of cigarette on its last breath in the ash pan. Nothing feels more American than driving down an open, empty highway at night. Where passing the glowing diner reminds us of our detachment from the cluster of people and passings. The passing of post-war commercial clutter indicated the entrance into the radioactive explosion of suburbia: the shopping mall, the drive-thru, the scattered billboards manifesting the next exit to be a mirror image of the one passed two miles ago. The exit designating home leads a steel skeleton of a car through street-lit dim lamps placed every 20 feet, revealing the perfectly manicured yards and colorful houses, when glancing into a window of the American family reveals a home-cooked meal prepared by a housewife. Be careful glimpsing turns into staring and staring turns into the stark reality of pulling into the driveway of a house wielded with an unilluminated window and no smell of pot roast. As we feel the reverberations of the industrialized fantasy that blurred the lines between consumerism and architecture, culture and capitalism, the ‘American Dream’ is no longer sustainable. Technology and industry are not necessarily villains, but how does design control these titans? Technology and industrialism must be reduced to the human scale to prevent each from becoming self-perpetuating, expanding monstrosities. Reclaiming the mammoths of past industry with the future of tomorrow waxes the scarring of the landscape with an omnipresence of human ruination remediation.

City Context:

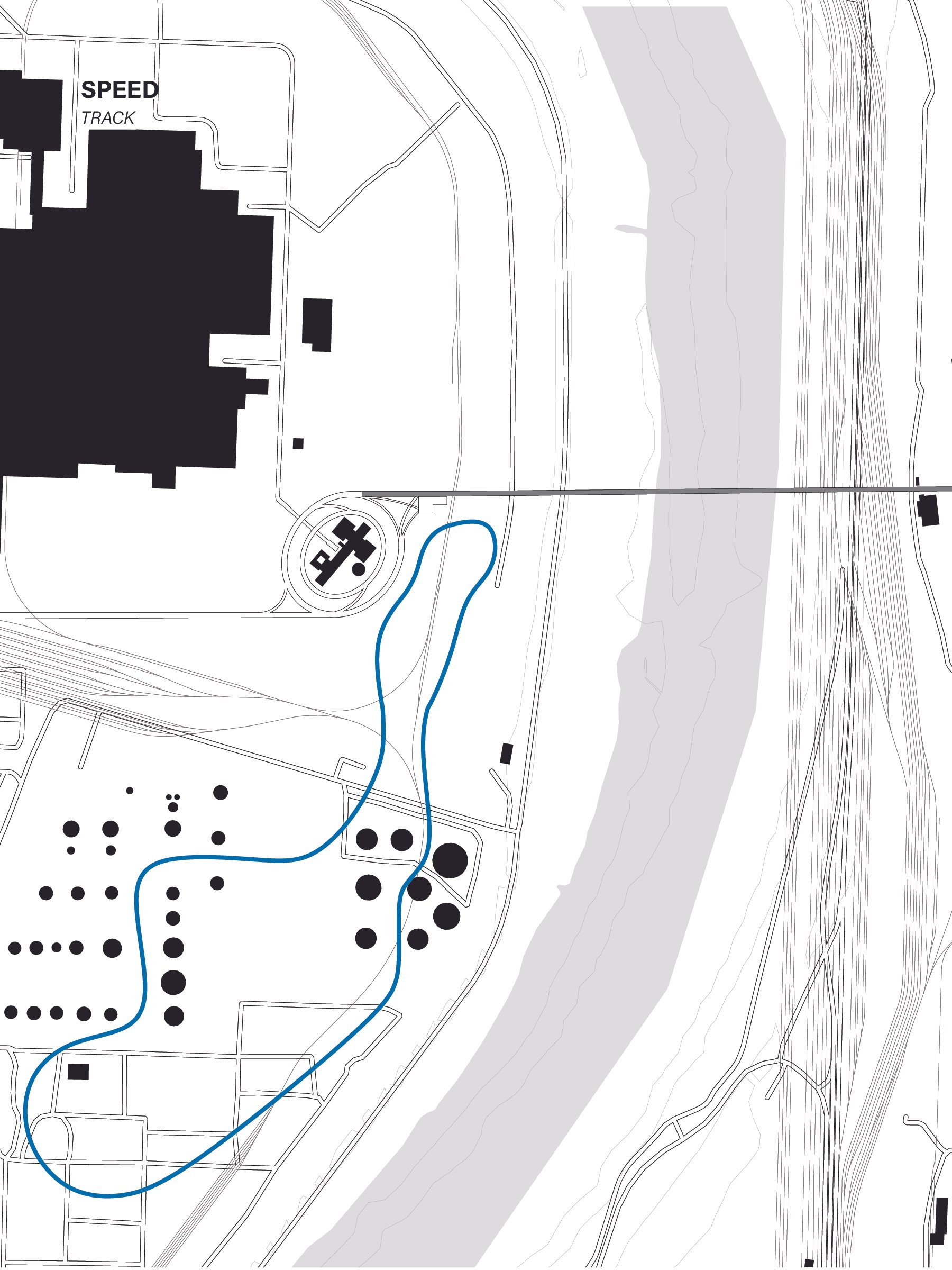

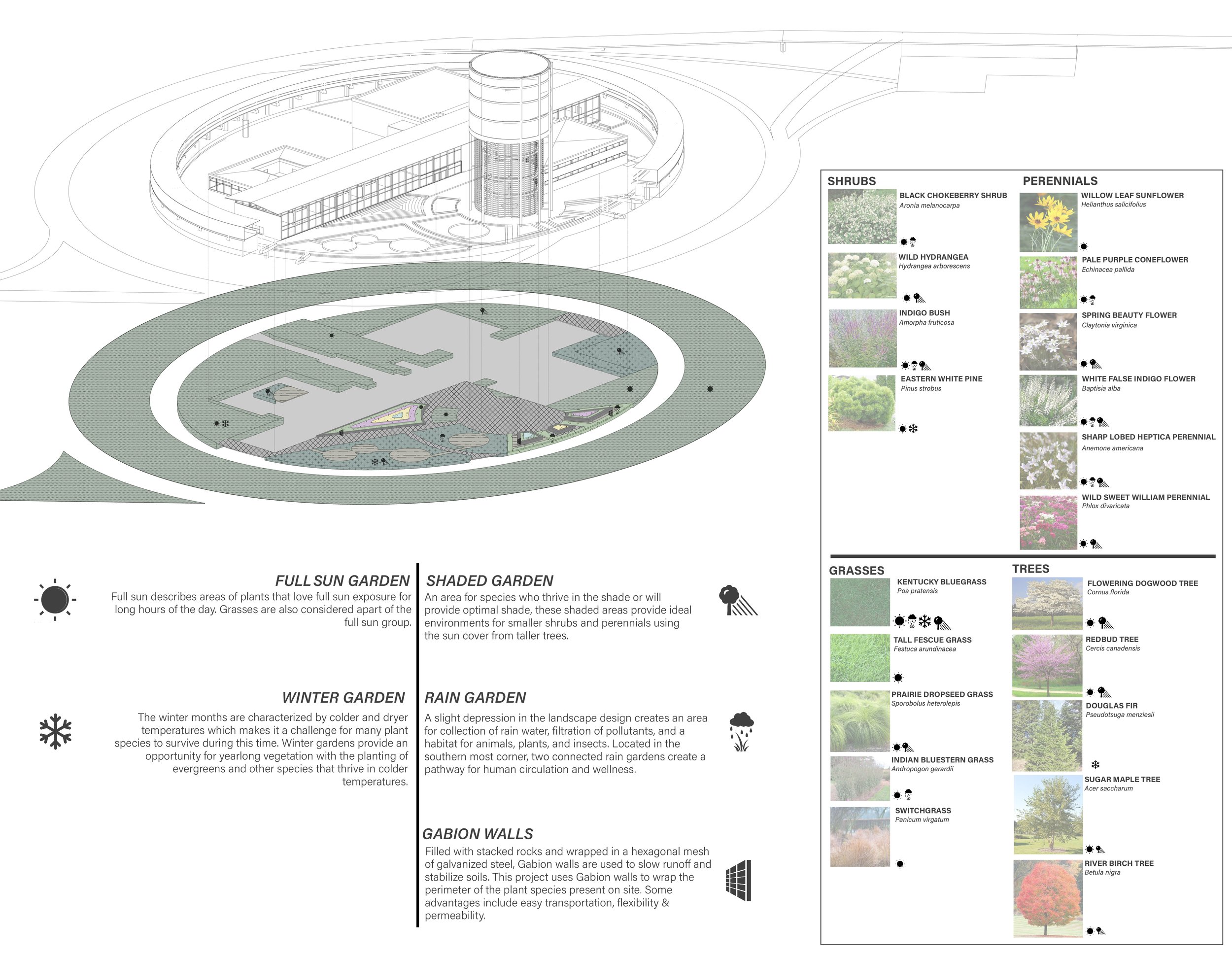

America’s Suburban Experiment in Microcosm shifted the once “Paris of the Plains” into a commuter city that is fractionated by the chaotic designed highway system. In the era immediately following World War II, Kansas City undertook—along with nearly the entire North American continent—a radical experiment in city building. Under this Suburban Experiment, the city built freeways and subsidized new home purchases, jump-starting suburban growth and unleashing a sort of geographic hyper-expansion even as the population of cities like Kansas City stagnated, and many of their older, inner neighborhoods fell into decline. Today, the Kansas City metro area, spanning parts of two states, has more freeway lane-miles per capita than any other major U.S. metro. Léon Krier describes the Suburban Experiment as a shift from organic expansion through duplication of an existing development pattern based on multi-purpose complete neighborhoods to horizontal hyper-growth, with the rise of a skyscraper district in the core dependent on suburban commuting. In present day, the urban core acts as a parking lot to the engulfing suburban borders. A car brand experience center amongst the land-locked nature of suburbia acts programmatically and spatially as a playground, negotiating that “ the space in between” point A to point B is the car. The presence of the unwalkable city surrounds its inhabitants and induces the machine as a design agent. Driving is the main source of transportation amongst the city-dwellers and annexed suburban households. Driving, the open highway, the feeling of solitude, provokes the action as a sacred ritual of the mundane everyday. One fails to notice the sanctified quality until a crisp gust of wind and the purring of the engine reveals the autumn scene devouring the landscape. The intersection of Americana and economically driven urban planning [or lack thereof] fuels Kansas City’s car culture. General Motors and its position within the community yields convergence of preservation of history and exploration into future technology. The project aims to reengage the riverfront and ecologically revitalize the brownfields within the “industrial” fallout district of Fairfax by constantly questioning the position that proceeded the existing architecture to provoke a more sustainable future.

Proposal:

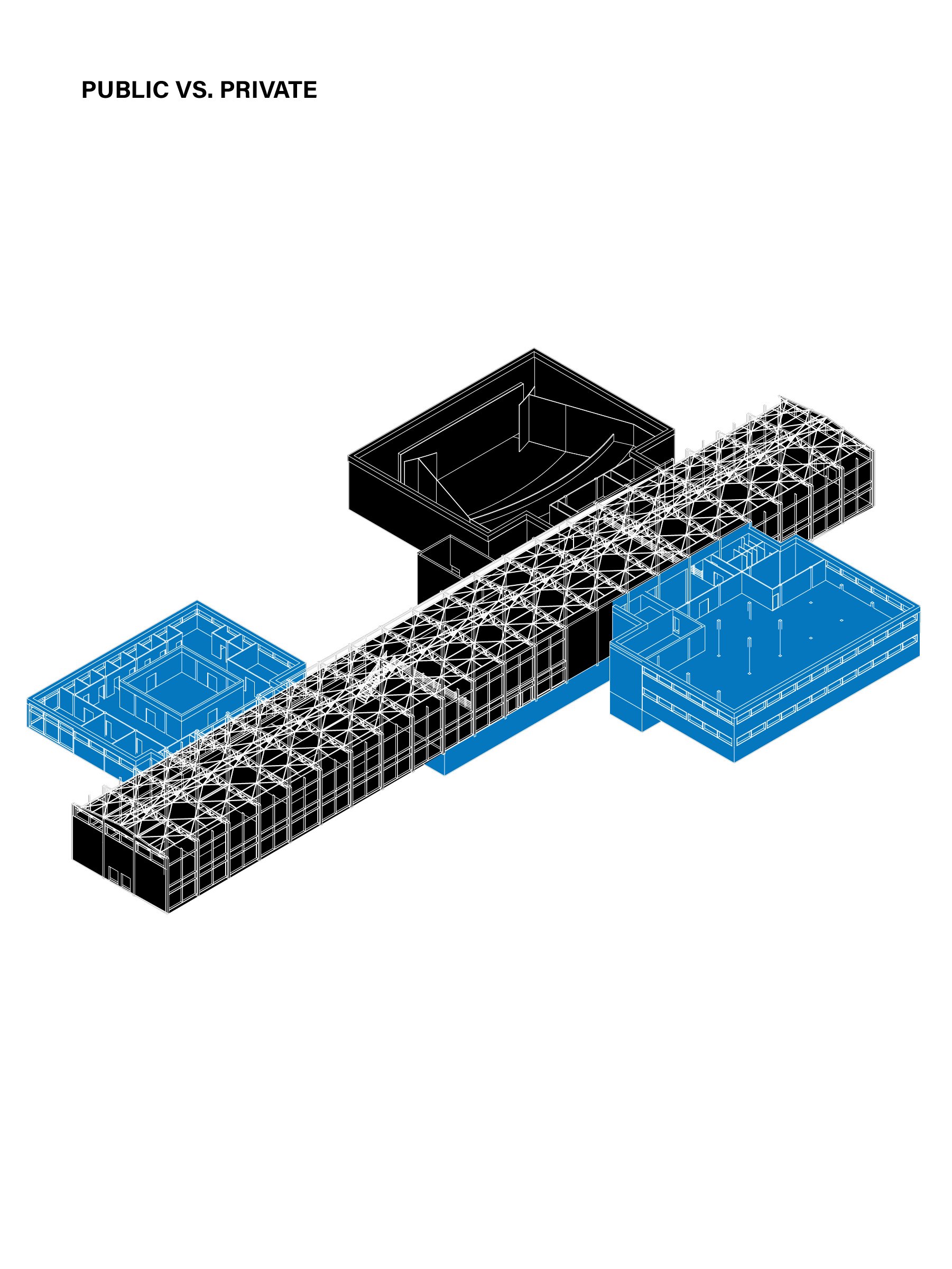

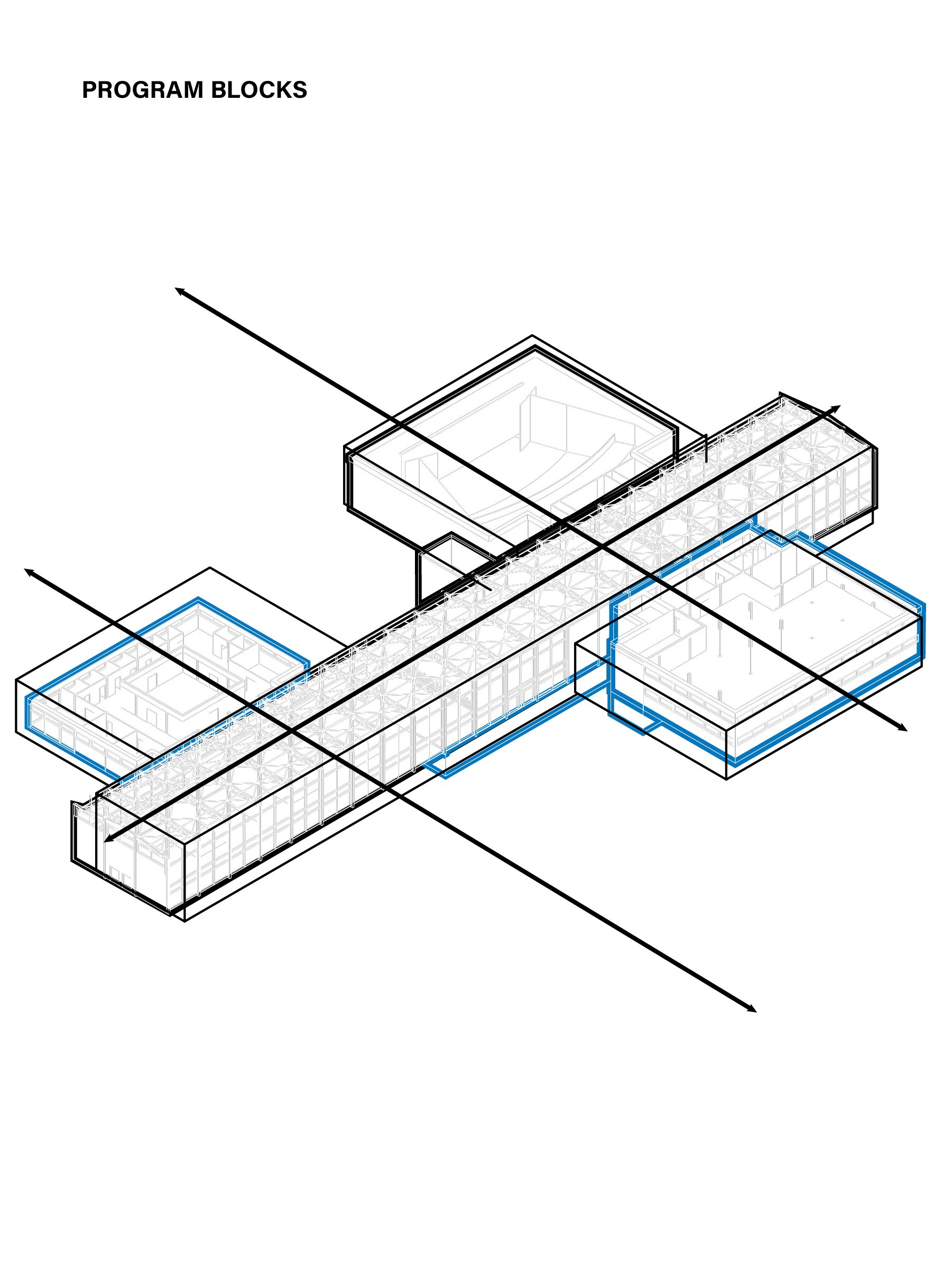

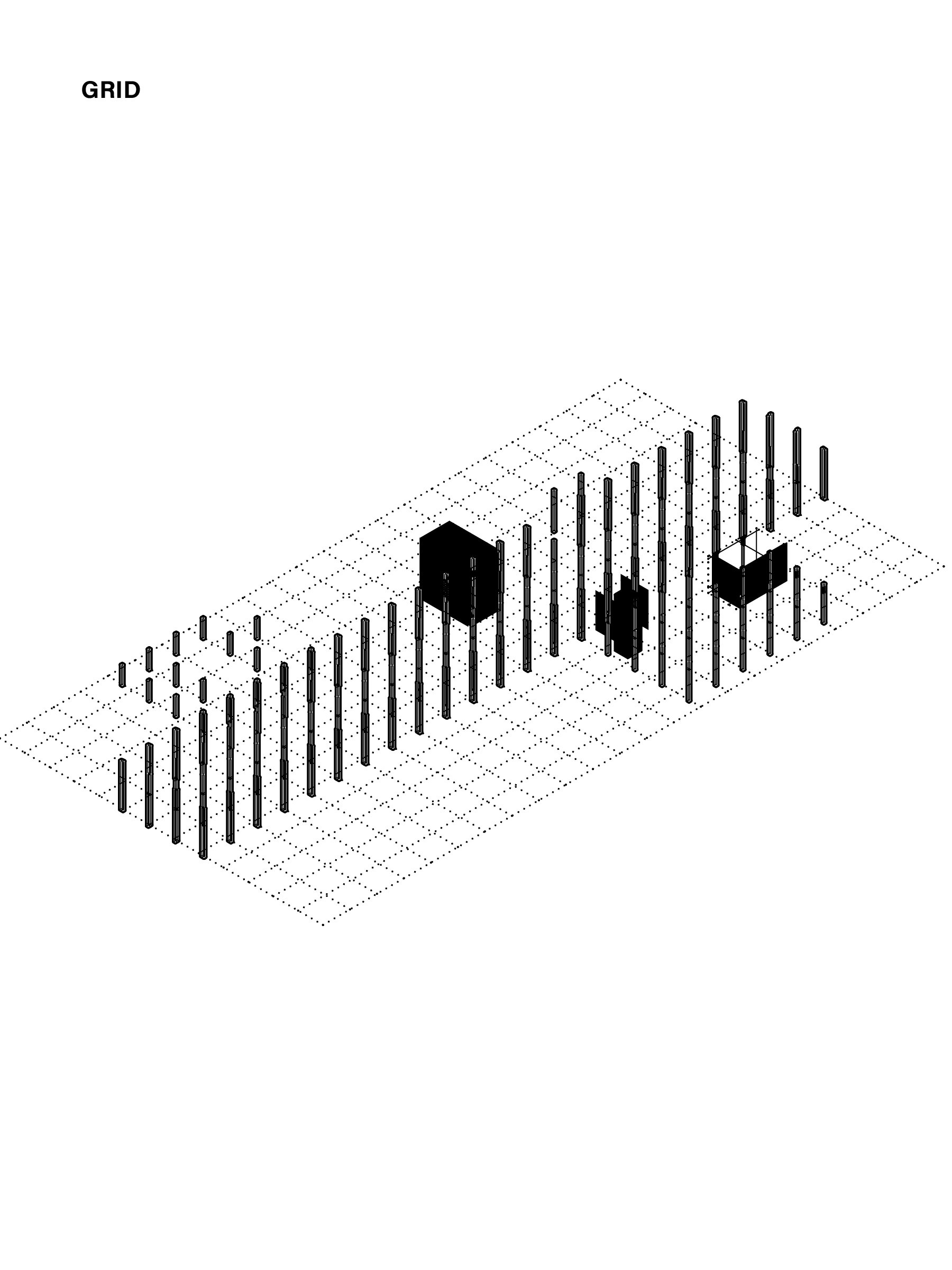

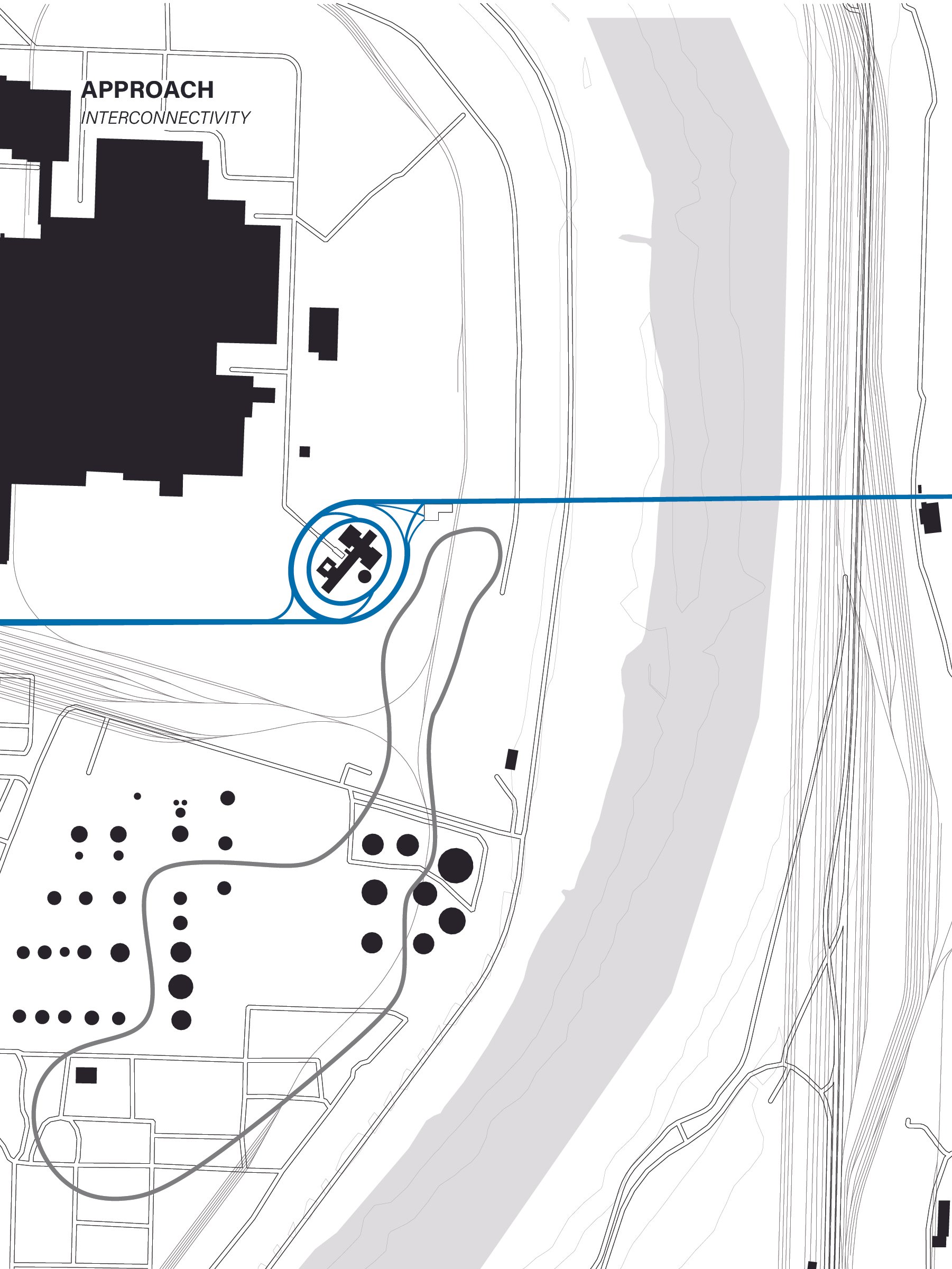

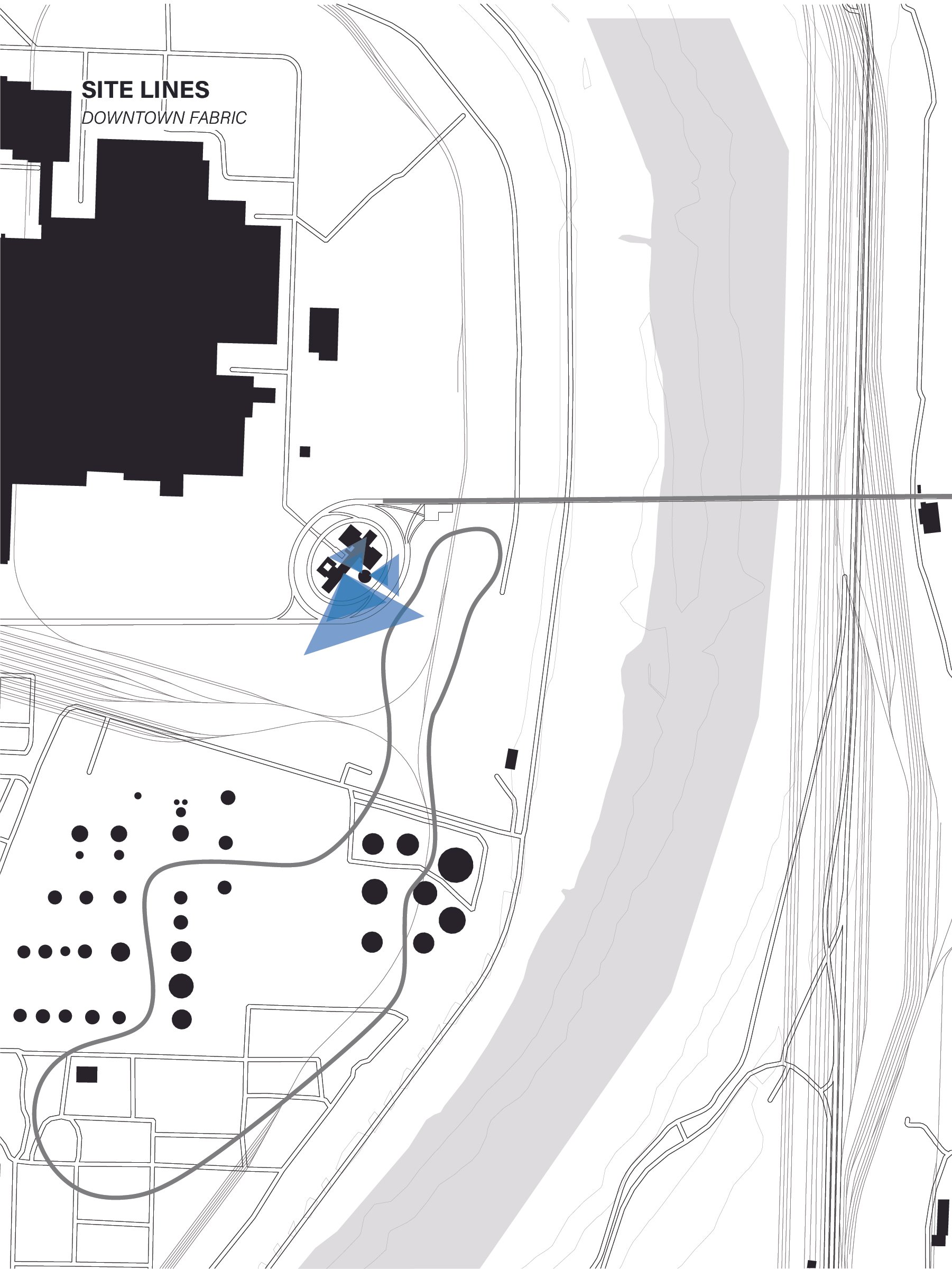

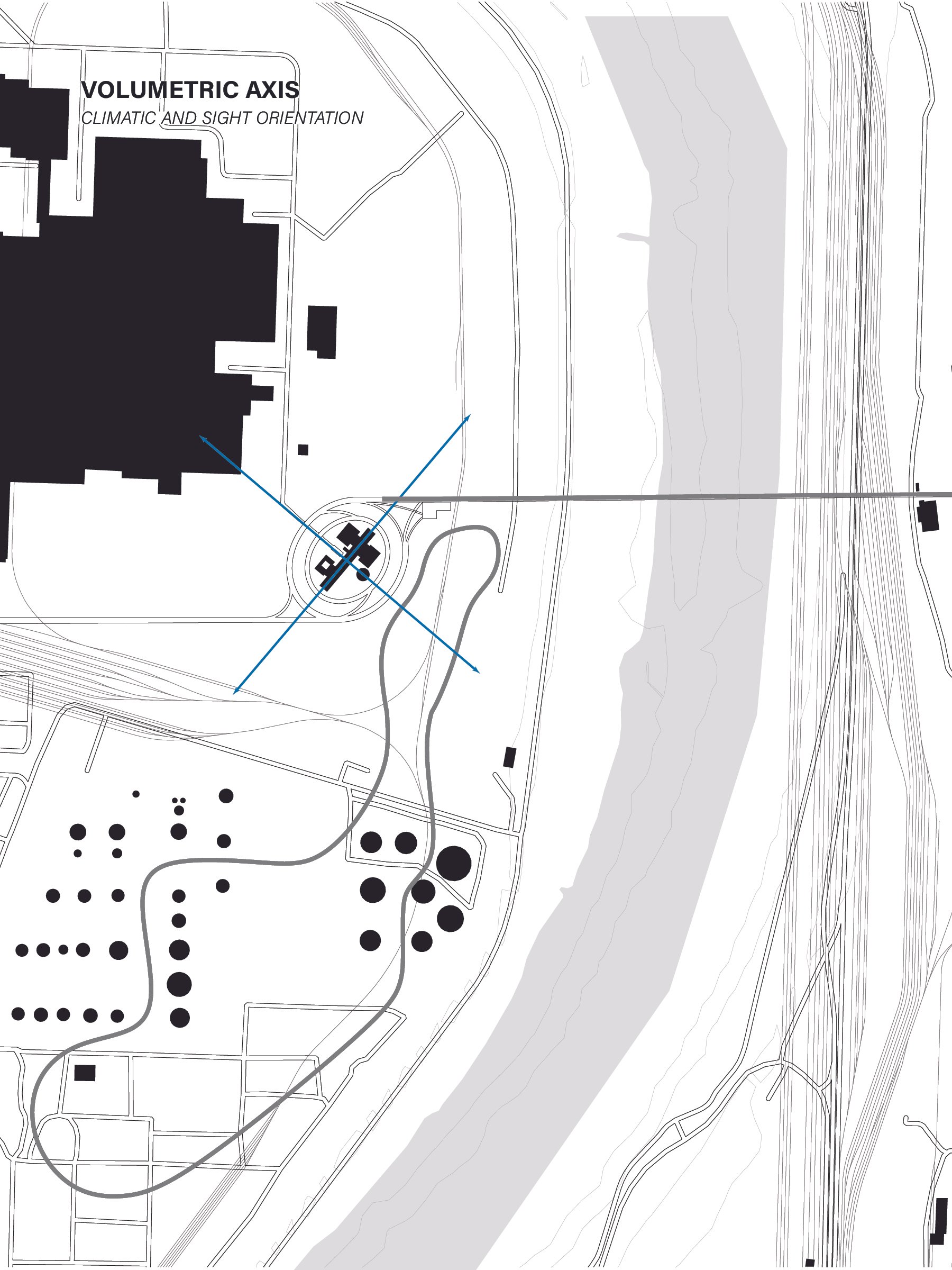

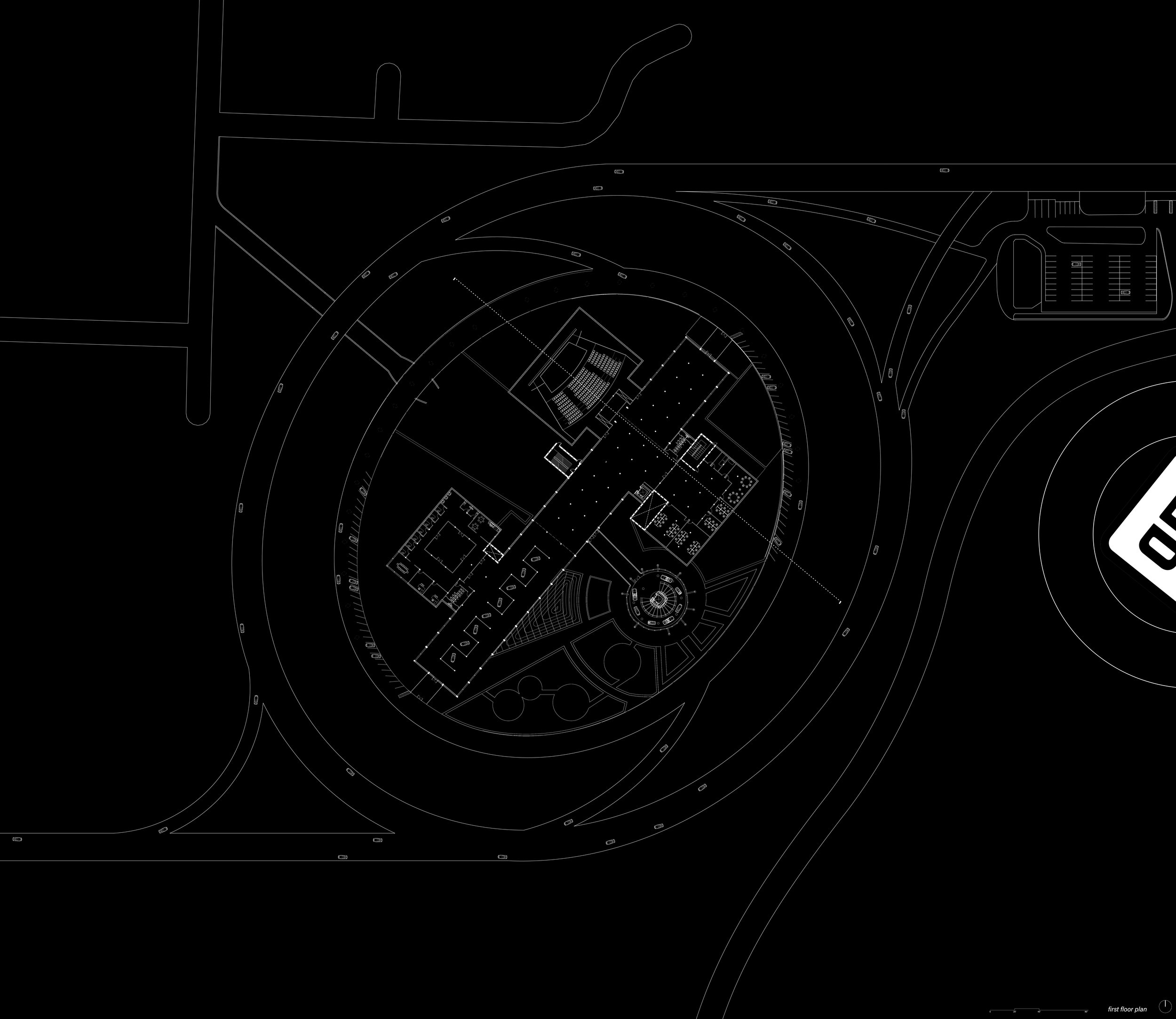

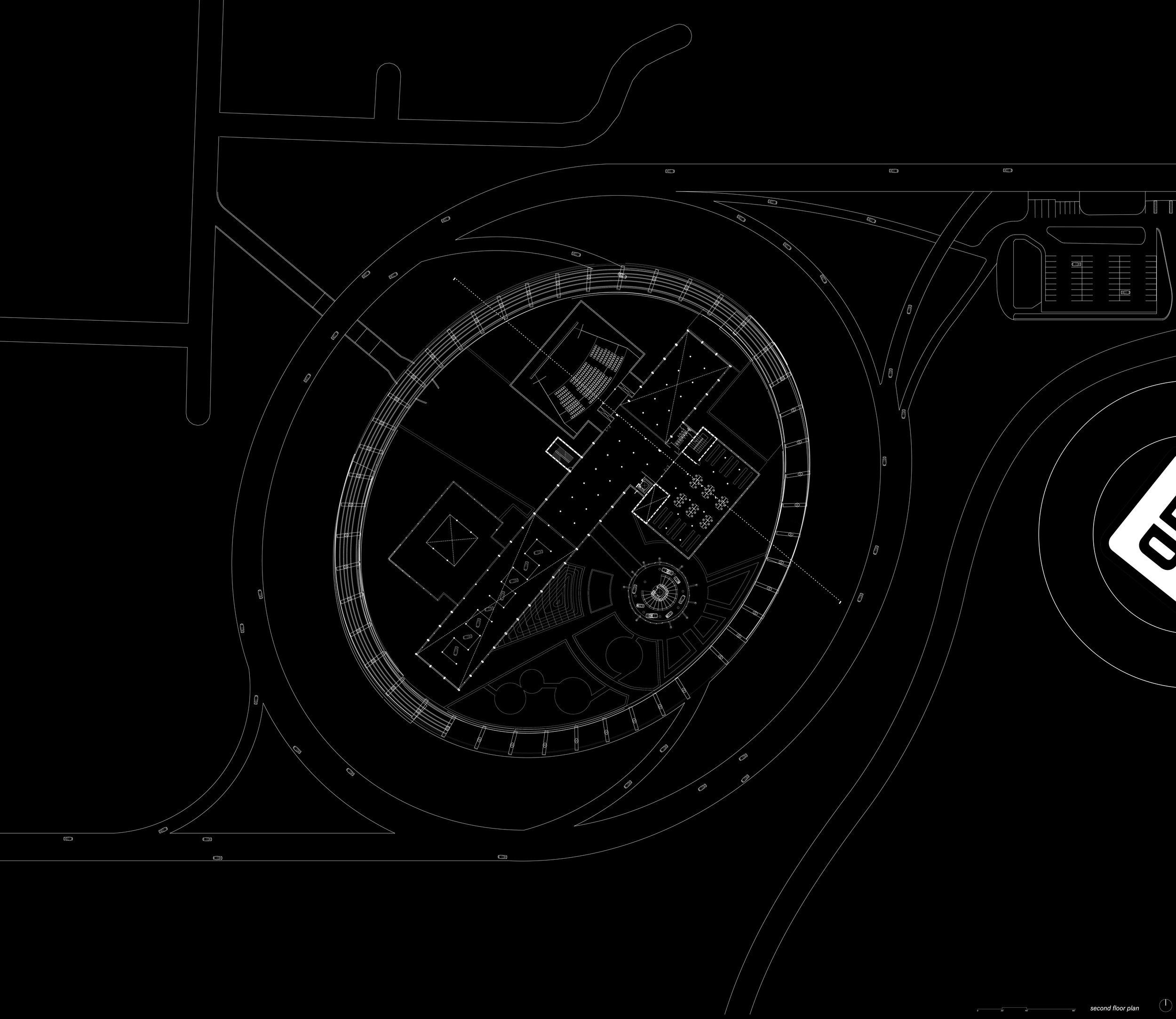

Establishing the main arteries forming the highway/interstate loop through the site, suburbia, the intermediate cityscape, and the actual cityscape recognized an intersection for an architecture to reside and be reduced to a highway and connection back to the riverfront and the downtown fabric. The circle is a direct response to the site context of connective arteries, and the proposed bridge is an agent to engage accessibility and mobility through the city. Lastly, we are approaching the project with the idea of phasing and that GM placing an architecture on the site and recognizing their responsibility of cleaning up the riverfront would allow the public to reclaim and re-program the riverfront zone, an extension beyond the experience center and redressing the ‘microcosm’.

We engaged the project with three independent conditions some relative to the site, some siteless conditions, some relative to cultural implications of cars.

Car culture:

The first trope we discussed was 1950’s car culture and its impact on the city and our perception of americana. During the 1950’s the car became a celebration of technology. Driving was an experience and shifted the landscapes we navigated today with emerging typologies of architecture catered to the car [ drive-thrus, drive-ins, highways, interstates malls]. And with this newfound mobility, ultimately, a freedom to explore… which is on the rise due to what one would presume to be covid and its recognition of living and working in the same spaces

GM identity:

The second condition was General Motors as a brand. The brand’s established roots became synonymous with pop culture [ in example the 1958 Chevrolet Impala in American Graffiti; however, GM today stands as almost indistinguishable from any other brand of equal magnitude. Restoring GM to the embodiment of their historical roots with the sustainable technology and image pushed by today’s narrative through an architecture becomes the main objective of the project.

Microcosm:

The last condition [what we define as Microcosm] arose from the statistic of Kansas City housing the most freeway lane-miles per a capita than any other major US metro. Vast clearing of the downtown fabric started within the city during the 1950’s and today encapsulate the idea of the car being the main form of transportation weaving through a once historical downtown to GM’s toxified industrial fallout zone of past industry. Kansas City [the microcosm] is an extreme example of what is occurring across the US and challenges us as architects to question how we reclaim this past manifestation of industry and settlement or housing.

Site:

So in the 1920’s GM took its first venture outside of Detroit into Kansas City on the east side of town. While this occurred an airport coined Fairfax resided on the site and later produced B-25’s for the war effort. Then in 1945 GM moved across town into the existing airfield and began building directly upon it. The action solidified the district into becoming a huge industrial zone headed by a 5 million square foot GM factory and immobilized the pre-existing redlined neighborhoods of Fairfax from downtown.

We preliminary established the main arteries forming the highway/interstate loop through the site, suburbia, the intermediate cityscape, and the actual cityscape and found an intersection for an architecture to reside and be reduced to a highway and connection back to the riverfront and the downtown fabric. The circle is a direct response to that, and the proposed bridge is an agent to engage accessibility and mobility through the city. Lastly, we are approaching the project with the idea of phasing and that GM placing an architecture on the site and recognizing their responsibility of cleaning up the riverfront would allow the public to reclaim and re-program the riverfront zone, an extension beyond the experience center.

Book publication: https://issuu.com/katiepennington/docs/integrations_book_reduced

![climate_cote map [Converted]-01.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/66816ccc980d50622fd8c9a8/cfcb18f9-2de0-44a8-a9aa-9c04739bb543/climate_cote+map+%5BConverted%5D-01.jpg)

![elevation [Converted]-01-01.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/66816ccc980d50622fd8c9a8/aede823d-28ff-479b-990d-dcd0b32aee9d/elevation+%5BConverted%5D-01-01.jpg)

![site plan [Converted]-01.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/66816ccc980d50622fd8c9a8/31c6dfd0-389f-40b8-9c68-9f2c66a1cc28/site+plan+%5BConverted%5D-01.jpg)

![axon [Converted]-01.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/66816ccc980d50622fd8c9a8/bb955443-6d23-4fa2-84c0-604303393636/axon+%5BConverted%5D-01.jpg)

![005 conference [Converted].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/66816ccc980d50622fd8c9a8/90f3d80e-8d4c-4b1e-8ebc-e622356fa5d5/005+conference+%5BConverted%5D.jpg)

![006 audi [Converted]-01.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/66816ccc980d50622fd8c9a8/163ba665-7379-420c-83e1-3a5fbe99383e/006+audi+%5BConverted%5D-01.jpg)

![007 library [Converted].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/66816ccc980d50622fd8c9a8/0a46b6fc-2176-45cb-80e0-91bee8e54b5f/007+library+%5BConverted%5D.jpg)

![008 track [Converted]-01.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/66816ccc980d50622fd8c9a8/31ec235d-6cc9-4d49-887e-cdd436f5d406/008+track+%5BConverted%5D-01.jpg)

![009 oil [Converted]-01.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/66816ccc980d50622fd8c9a8/11aea060-5bcb-4c7d-809e-5bb6abca7c1d/009+oil+%5BConverted%5D-01.jpg)

![building section [Converted]-01-01.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/66816ccc980d50622fd8c9a8/b496d486-2211-4bbc-a712-0e9a89ae6770/building+section+%5BConverted%5D-01-01.jpg)

![perspective 001 [Converted]-01.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/66816ccc980d50622fd8c9a8/a02c518d-6686-441e-ba86-5965daf9aac1/perspective+001+%5BConverted%5D-01.jpg)

![perspective 002 [Converted]-01.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/66816ccc980d50622fd8c9a8/89aecaf5-0ec7-4d1b-92b1-e0df1854cfd3/perspective+002+%5BConverted%5D-01.jpg)

![perspective 003 updated [Converted]-01.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/66816ccc980d50622fd8c9a8/49acacb6-fdbe-4b0c-aed0-84d1f12cf8e9/perspective+003+updated+%5BConverted%5D-01.jpg)

![perspective 004 [Converted]-01.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/66816ccc980d50622fd8c9a8/591363d8-bc4f-47c3-a84d-b934f95e7abe/perspective+004+%5BConverted%5D-01.jpg)